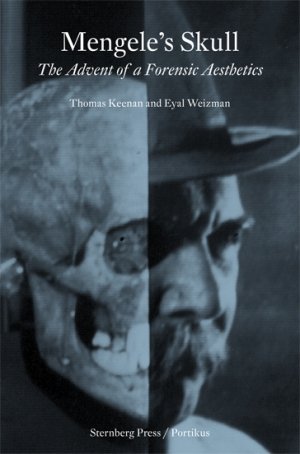

Mengele's Skull: The Advent of a Forensic Aesthetics

In 1985, the body of Josef Mengele, one of the last Nazi war criminals still at large, was unearthed in Brazil. The ensuing process of identifying the bones in question opened up what can now be seen as a third narrative in war crime investigations—not that of the document or the witness but rather the birth of a forensic approach to understanding war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In the period coinciding with the discovery of Mengele’s skeleton, scientists began to appear in human rights cases as expert witnesses, called to interpret and speak on behalf of things—often bones and human remains. But the aesthetic, political, and ethical complications that emerge with the introduction of the thing in war crimes trials indicate that this innovation is not simply one in which the solid object provides a stable and fixed alternative to human uncertainties, ambiguities, and anxieties.

The complexities associated with testimony—that of the subject—are echoed in the presentation of the object. Human remains are the kind of things from which the trace of the subject cannot be fully removed. Their appearance and presentation in the courts of law and public opinion has in fact blurred something of the distinction between objects and subjects, evidence and testimony.

Co-published with Portikus, Frankfurt am Main

Design by Zak Group

25 color ills., 24 b/w illustrations.

- Forlag: Sternberg Press

- Utgivelsesår: 2012

- Kategori: Poesi

- Lagerstatus: Ikke på lagerVarsle meg når denne kommer på lager

- Antall sider: 88

- ISBN: 978-1-934105-91-7

- Innbinding: Heftet